Climbing on wet sandstone or other porous, softer rocks is more than just an inconvenience—it can cause irreversible damage. Sandstone soaks up moisture like a sponge, weakening the mineral bonds that hold grains together. Even if the surface feels dry, water trapped deeper in the rock remains, making it soft and crumbly under load.

“While staying off the stone for 24 to 48 hours after it rains is a no-brainer, many factors such as aspect, wind, season, and amount of precipitation have an impact on how long it will take sandstone to truly dry off and be safe to climb again.”

— Access Fund (Access Fund)

How Moisture Weakens the Rock

When rain or snow hits sandstone, the cementing agents that bind grains break down as water infiltrates. Under a climber’s weight or impact from a fall, holds can snap off unexpectedly. Laboratory tests show that mechanical strength can drop 15–75% when saturated, depending on the rock’s composition and how long it was soaked (Berkeley Biomechanics).

In practice, this means:

- Surface dryness ≠ safety. A sunny afternoon might dry the outside in hours, but the interior can stay wet for days.

- Fracture risk. Softened rock can fracture under normal climbing forces—holds that used to feel solid can crumble.

- Long-term wear. Even minor chipping accelerates erosion, permanently altering classic lines.

Rock Types That Dry Quickly

Not all rock behaves like sandstone. If you’re itching to climb soon after a shower, look for non-porous, crystalline rocks—think granite, basalt, and quartzite—which have much tighter mineral bonds and shed moisture rapidly. Classic granite walls at places like Yosemite’s Camp 4 or Eldorado Canyon often dry out within a few hours on sun-soaked faces. Similarly, the dark basalt columns of Smith Rock and the dense quartzite boulders of Bishop’s Buttermilks can be climbable the same day (as long as there’s good airflow and direct sun). Even some limestone crags—such as those in Red River Gorge—have sections that drain fast, especially on overhanging tiers. Of course, always verify local beta: aspect, recent precipitation, and wind all play a role, so when in doubt, give it an extra day.

Real Incidents of Wet-Rock Damage

Echo Chamber (Hueco Tanks, TX)

After a spring rainstorm, a visiting party climbed the “Echo Chamber” boulder on West Mountain—despite warnings to stay off wet rock. As one climber topped out, a key hold broke, sending him over the pads. He suffered two broken legs, shattered heels, and lasting complications that ended his career.

“Twenty years of climbing ended swiftly with the stupidest decision of my life to climb on the last day of my trip, even though it had rained the day before. Don’t f#%@ing climb after it rains because the rock become more brittle.”

— Omar, Climbers of Hueco Tanks Coalition (Non Profit)

Accelerated Wear on Gritstone (UK)

Although not sandstone, UK gritstone behaves similarly when damp. A recent Depot Climbing report warns:

“We’re increasingly seeing the damage and accelerated wear on gritstone boulders due to totally avoidable bad practices around wet rock. The single biggest thing any of us can do to be good custodians of gritstone boulder problems…is:

Only climb on completely dry rock.”

— Depot Climbing (Depot Climbing)

This principle applies equally to softer sandstones in Red Rocks, Joe’s Valley, or Indian Creek.

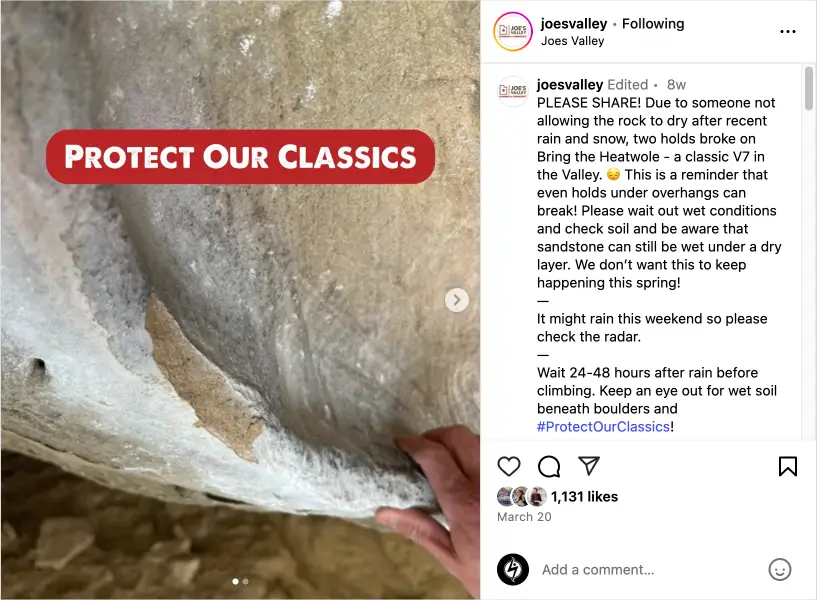

Bring the Heatwole (V7), Joe’s Valley, UT

The Joe’s Valley Climbing & Community Instagram and a parallel Facebook post reported that two holds on the classic Bring the Heatwole had snapped off after someone climbed it only hours after rain and snow. As the community reminded everyone, “PLEASE SHARE! Due to someone not allowing the rock to dry after recent rain and snow, two holds were broken on Bring the Heatwole—a classic V7 in the Valley.” (Facebook, Instagram)

They Call Him Jordan (V7/V8), Joe’s Valley, UT

A Mountain Project thread where, on August 29, 2018, a climber posted a photo titled “Gaston Broken? 8/29/18,” showing that the key gaston hold on They Call Him Jordan had fractured. Though no formal incident report exists, this firsthand account underscores how even well-trodden classics can suffer permanent damage when climbed before the rock has fully dried (mountainproject.com).

Why Climbers Push It

- Short-trip pressure. Road-warriors squeezing a weekend often ignore local ethics to tick a bucket-list problem—only to find the rock still “moist inside.”

- Perfect weather windows. A sunny forecast after days of rain can feel like a golden opportunity. Unfortunately, the exterior dries before the interior.

- Social-media urgency. Climbers chasing Instagram sends or YouTube content sometimes prioritize footage over stewardship—despite countless reminders not to climb wet rock.

Even major gear brands acknowledge the temptation:

“For sandstone to dry quickly (i.e. 24 hours), the ambient air temperature should be above 70°F, your intended climb should have a southerly aspect, and there should be a breeze.”

— Mountain Hardwear (mountainhardwear.com)

Best Practices for Protecting Porous Rock

- Check recent precipitation. Before any sandstone trip, look up hourly forecasts and talk to locals or land-managers.

- Inspect the base. If you see pooled water, muddy pads, or damp sand around the talus, wait another day.

- Follow local closures. Parks like Hueco Tanks now impose blanket bans after rain—respect them.

- Spread the word. Remind your partner groups and post on forums: a friendly heads-up can save a classic problem.

The Bottom Line

Sandstone and other porous rocks are living canvases shaped over millennia. A single ill-timed climb can shatter holds, degrade the crust, and rob countless climbers of an authentic experience. By waiting 24–48 hours (or longer, in cool/humid conditions), you ensure that your send doesn’t become someone else’s vandalism.

“It is never worth rushing: The route will be there … as long as the holds don’t break.”

— Access Fund (Access Fund)

Ready to climb responsibly? Plan your next sandstone outing with patience built in, share these guidelines with your crew, and help preserve our favorite crags—one completely dry hold at a time.

Looking to plan your trip to a sandstone mecca? Check out our guide on Joe’s Valley.