Climbing Inclusivity

This past spring and summer, the BLM protests sparked racial and social justice conversations throughout the US. These conversations made their way to the climbing community.

The big question for us in the climbing community was: How can we make outdoor spaces more inclusive for everybody? How can we be anti-racist in the outdoors?

Around that time, Genevive Walker was able to change several racist route names in Ten Sleep, WY. This set a precedent.

Stevie Imperatrice, Zoe Brown, and I (Lucy Vollbrecht), local Flagstaff climbers, began talking about problematic route names in Northern Arizona. There were certainly some problematic local names. Therefore we thought that Northern Arizona climbers would endorse a community-based route renaming effort.

What Difference Will Route Renaming Make?

It is ethically complicated to rename routes. The thought is that when someone encounters a discriminatory boulder or route name, it perpetuates negative stereotypes. This acts as a gate-keeping mechanism and as a barrier to some climbers.

Names that use negative stereotypes enforce the idea that only a specific climber is a “real” climber. These names communicate that climbers of whatever targeted social demographic don’t belong in that space or the sport. For example, calling the warm-up wall, the Girlfriend Wall enforces the idea that women don’t climb hard and that they don’t climb for themselves. The only reason a woman would come out to climb is as a partner to their boyfriend. This is not true.

More generally, calling a problem a discriminatory name – for example, “F****** Retard” or “N***** B****” – enforces the idea that these spaces are ones in which discrimination is the accepted norm. Calling climbs by racist, sexist, and ableist names (and by retaining these names now that their discriminatory nature is widely evident) signals to individuals who belong to those historically marginalized groups that a given space is one of continued marginalization. It isn’t for them. The prejudiced norms of society at large are still in play here.

The motivation to change problematic route names is to make these spaces and activities we love more inclusive and welcoming to everyone. We shouldn’t be perpetuating practices that keep others away because of who they are.

Community-Based Action

After deciding which names and why this work was necessary, we began the process of route renaming. Our biggest priority with how we implemented this project was making sure this was a community-wide initiative. Not just a couple of people deciding on new names. We wanted to include as big a swath of the local climbing/and wider climbing community as possible.

We decided to start with relatively few route names and chose what we deemed the worst offenders. Therefore, I won’t refer to the routes by their old names here. Still, there was overt racist language, racially charged hate speech. These came as references to violence against the native community, references to violence against women, and derogatory slur towards disabled people. All of these names we thought to be utterly inappropriate because of the long history of violence against native people, the black community, women, and disabled people.

Crude vs. Discrimination

The issue we are trying to navigate here is censorship. The goal is to filter out racist, misogynistic, ableist, or otherwise socially unjust names. But NOT filter names that are simply crude (that is, names that include a swear word or allude to sex acts). Names that iterate the oppression of peoples based on social identity are the issue, not potty language.

What at first seems like a vast grey area is no more complicated than asking the question, “Is this name just vulgar/crude/immature, or does it discriminate against an entire community of people?”

Survey

We consolidated our efforts within Priest Draw, an area we are very familiar with. In a lot of cases, we know the context behind many of the route names. Then reached out to local gyms and NAZCC to get community buy-in and help to disperse a survey we developed.

We created the survey to get name suggestions for the five routes we picked from the wider community. There were over 100 suggestions for each name. Included was a section where community members could share personal stories and thoughts on why renaming these routes was essential to them. In addition, a wide range of shared anecdotes/stories about how harmful/discriminatory route names can be.

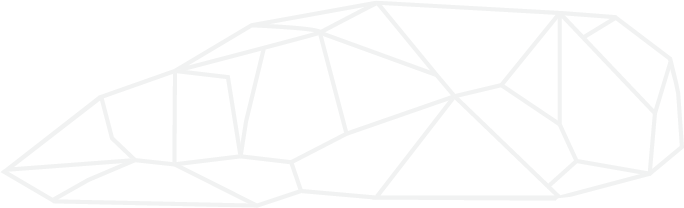

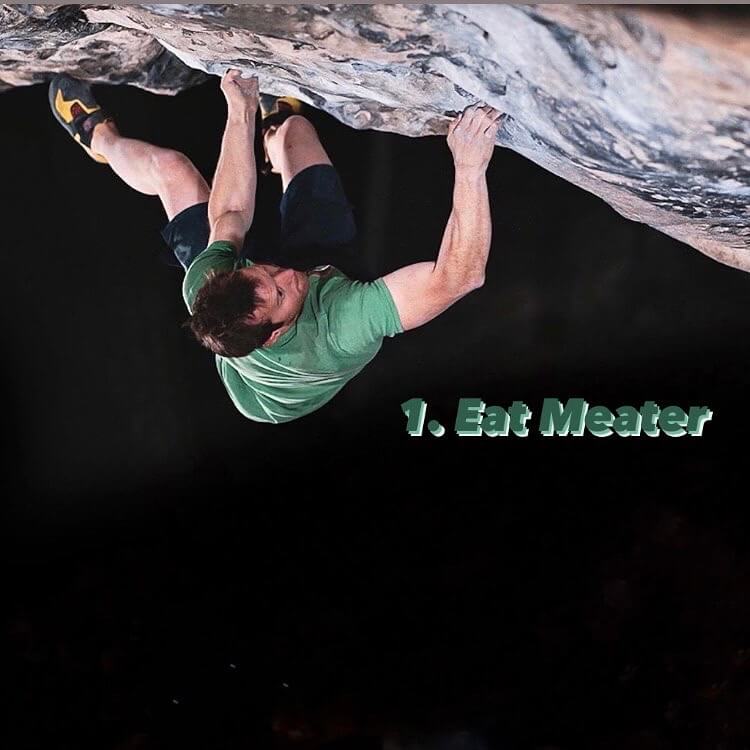

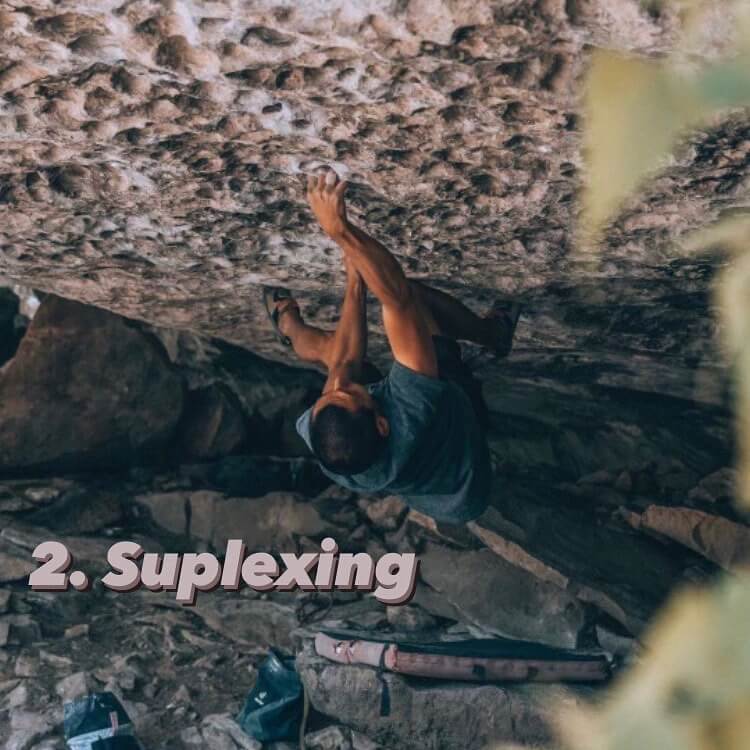

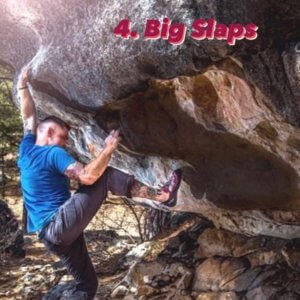

We then sifted through over 500+ new name suggestions for the five problems from the new community suggestions. We condensed these into 4-5 finalists that we felt best represented each climb and the community’s voice. Remarkably, many suggestions were quite similar or fit into a common theme. Then we put out a 2nd survey for the community to vote on final names. We had over 200 votes for each new name.

Our next step was to see these changes reflected on Mountain Project—which they now are — and work on changing the names in the local PDF Guide.

Anecdotes from the initial survey:

“Misogynistic names remind me of how hard it has been to prove myself in this sport and how uncomfortable it was to be in the community until I did. I felt I was not worthy until I started climbing “hard,” and I still see my girlfriends being dismissed based on their gender and the grades they climb.”

“While teaching a friend to lead at the Panty wall in Red Rocks, a group of Bro’s heckled us to show them our panties. The entire day. My friend ended up in tears from the stress of leading her first route outdoors and being harassed nonstop by strangers.”

“As a white male, I’ve never felt personally targeted by it, but some route names do make me ashamed to be a climber and feel complicit in the exclusive environment that is climbing.”

For us, these anecdotes, and the more we received, show that this project is worth the effort. It proved that route renaming can and does have an impact on the people who climb them. Of course, this is only the start to working towards an anti-racist and more inclusive climbing community, but it is a start.